Judicious use of Pennsylvania and Missouri wood yields four distinctive C. Elizabeth Wines vintages.

Mentioning American oak to some oenophiles prompts a mad dash to the (forested French) hills, but a recent home tasting of the initial C. Elizabeth Wines Game Farm Vineyard Oakville Cabernet Sauvignon vintages (2014–2017) illustrated how misguided blanket statements about wine can be. In the judicious hands of winemaker Bill Nancarrow, four distinctive wines, aged in wood mostly from Pennsylvania but also Missouri, emerged.

Passion Project

C. Elizabeth Wines is the self-described passion project of Dave Ficeli and Christi Coors Ficeli, both industry veterans, he previously of Jackson Family Wines (Napa Valley and Carneros brands), she formerly of E&J Gallo and now her boutique winery Goosecross Cellars. Christi is also a scion of the Coors beer-making family.

Nancarrow, who hails from New Zealand, crafts the Goosecross wines as well; stops before Goosecross and C. Elizabeth include the Napa Valley’s Duckhorn Vineyards and Pask Winery in his native land’s Hawkes Bay. C. Elizabeth makes only the Game Farm Cabernet each vintage. The winery’s name honors several Elizabeths on Christi’s side of her family, including herself (Elizabeth is her middle name).

Viticulture in Winemaking

Winemakers often talk about wines being “made in the vineyard.” Sipping the Cabernets the night before a Zoom presentation for wine journalists by Dave, Christi, and Bill, moderated by sommelier Chris Sawyer, I’d picked up on the fullness of mouthfeel, especially in the last two wines. “No holes anywhere,” read my notes.

I’d planned to ask Nancarrow what he’d done in the vineyard or cellar to achieve the wines’ mouthfeel, particularly given that all C. Elizabeth vintages are 100% Cabernet. (Among other maneuvers, winemakers sometimes blend in Merlot, Petit Verdot, Malbec, or other grapes to fill in a Cabernet’s gaps.) As it happened, the winemaker addressed the topic in the presentation.

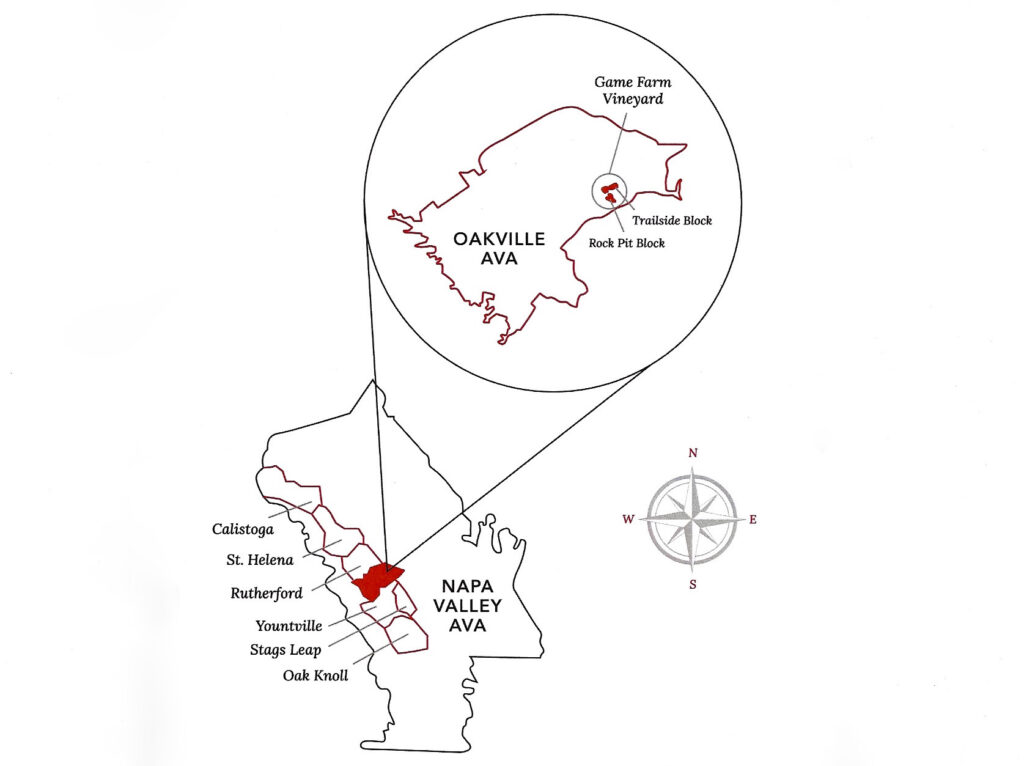

The first two vintages came from Game Farm Vineyard‘s Rock Pit Block. As the block’s name suggests, it’s rocky, imparting an inescapable minerality to the wines. In 2016, Nancarrow had access to grapes from the Trailside Block, which though rocky has an iron-rich topsoil layer. “I wanted to see if the fruit from there would actually give the wine a little more mid-palate fleshiness,” he said. “I wanted to see if we could get this from Game Farm . . . rather than create it in the winery,” favoring viticulture over cellar technique to accomplish the goal.

Tasting Impressions

Collectively, as might be expected the classy C. Elizabeth Cabs told the stories of their vintages and vineyard. But they also spoke to the evolution of Nancarrow’s understanding of both Game Farm Vineyard and American oak—the C. Elizabeth wines represent his first foray into winemaking solely using such barrels. Seeking subtler effects from the oak, for instance, Nancarrow began in 2015 using some water-bent barrels (as opposed to ones shaped by fire or steam) with thin staves from wood seasoned four years instead of the more common two or three.

The likable 2014 still had plenty of fruit for a six-year-old wine, which bodes well for the newer ones’ ageability. The 2015, perhaps because its vintage was the last of a four-year drought, the scarcity of water resulting in higher skin-to-juice ratios and thus more concentrated flavors, was the delight of the group for its lively tannins and back-palate spiciness. At a little over five years old, it was at a nice stage in its development.

I noted with all the bottles that the longer they were opened, the more I liked the wines. Not to be churlish, but American oak’s dill and other herbaceous components don’t always work for me, especially with Napa Valley Cabs. Fortunately, the effect dissipated as contact with oxygen increased. This was especially the case with the 2016, which I came to like rather much.

Though the 2017 was young and a tad tight, I appreciated the wine’s red- and blue-fruit characteristics and long finish that rivaled the 2015’s. Nancarrow said that the blend contained more Trailside fruit in 2017 than 2016 and that to preserve the vintage’s “delicate fruit” he’d used less new oak during aging, upping the number of neutral (previously used) barrels, which impart fewer wood flavors. (The 2016 received 85% new oak, the 2017 only 30%.) I’ll be curious to see if the winemaker sticks with this strategy of reduced new oak in future vintages. In general, it seems the right approach.

Lead photo of Game Farm Vineyard courtesy of C. Elizabeth Wines.

Pingback: STORY INDEX BY REGION – Daniel Mangin